ARTWEEK, August 24, 1974 •

by Martha Alf •

Referring to himself as an “art peddler,” dynamic, Los Angeles-based art dealer Nicholas Wilder spoke in May (1974) to an informal gathering, composed mostly of students, but also attracting some other art world enthusiasts, on the UCLA campus. It was the last in a series of such talks organized by UCLA sculpture instructor, Rita Yokoi.

Wilder, nattily dressed in blue with silver lamé socks, began by asking for questions other than those which could be answered by art history or studio faculty: questions that he as an “art peddler” would be most apt to know.

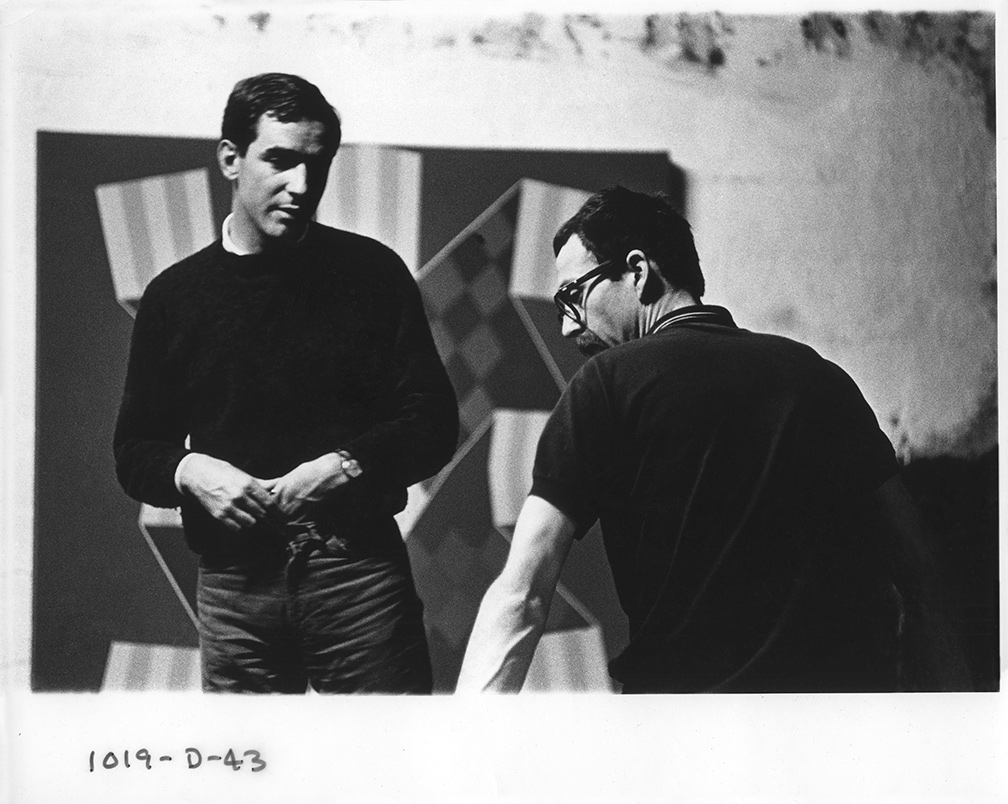

Nicholas Wilder and Ronald Davis, 1965.

Is it necessary to live in New York to achieve success as an artist, and is New York art valued over Los Angeles art?

I don’t feel it as much now . . .

What is the value of an art school education?

The first value is keeping males out of the draft. In addition, it puts aspiring artists next to other artists — their professors. The students can make their art in proximity to someone who is really involved in making art, worrying about their shows and so on.

Do you believe in contracts for artists?

A dealer can’t make an artist paint under duress. I only do a contract if an artist wants it. The residual rights idea with Bob Rauschenberg and Bob Hughes is just beginning. As far as exclusivity, on artists just starting out, I have complete world exclusivity. Later, I let my artists show in other areas, such as San Francisco, without requiring part of the commission — as long as the artist lets me know so we can discuss it.

Do you show the same stable of artists, or change?

I hate the word stable — it always sounds like a bunch of horses. I show too many artists. Three weeks’ exposure every year isn’t needed for the Agnes Martins or Kenneth Nolands, but the newer artists in my gallery should show every year or 18 months.

How does a new artist just ouf of school get started? Is it by knowing friends who are more established or through recommendations?

The new artists should just get in their studios and work. The major corruption in the unjust art world is 99% on the part of the artists in now understanding what’s going on and their misconceptions in thinking that to be shown, written about and otherwise promoted makes the art work any different. It doesn’t make the art work any different. First, art work is made in the studio.

How about discrimination against women in the art world?

In regard to democracy in art, there was a women’s-group study by June Wayne that purported to show so much discrimination on the part of dealers and writers against women. I asked the women who show in my gallery, Agnes Martin, Jo Baer, Helen Frankenthaler and Joan Snyder, and they feel no discrimination. I think there should be more artists that just happen to be women. I think it’s a sociological thing based on the educational system.

What determines whether a person is an artist?

Who is an artist boils down to self-appellation. They say “I am an artist.” I don’t believe there is a right that artists should live off their art. I don’t believe in mistakes in art good or bad.

How does an artist become visible after working hard in the studio and now has a large body of work?

There must be people in the community who would like to become familiar with their work. I want other art galleries to open in Los Angeles so I can go look at art there anonymously, for my own enjoyment, with the pressure off. With a new artist I’ve never seen before, I start by looking at slides in my gallery. Some artists want me to talk endless hours to them. If I did, I would soon be out of business. I saw seven artists today and didn’t get in the gallery until ten after two. It was a typical day. When visiting a new artist in his studio, I sometimes see what’s going on immediately. When things perplex me and come back and haunt me — those interest me. I have a built-in alarm that goes off when I like something immediately — a warning device.

How do you judge a dealer?

You judge a dealer on what he has to sell and on what he’s sold. Betty Parsons, for example, had Pollock, Agnes Martin, Newman, Rothko, Still — everyone but de Kooning. If Betty Parsons told me to look at an artist or even to buy something sight unseen, I’d do it. What a dealer does results in increased prices: deals with other dealers, artists, writers, critics, museums. As an artist’s work is seen more, bought more, it thus becomes scarce for more buyers, forcing prices up. It’s not anything qualitative that forces prices up, but rarity. Joe Goode’s “Windows” 10 years ago were $300. If you can buy one now on the open market for $10,000 please tell me. A lot of prices in the art market are fictitious. For example, here is how it works: with the beginning Francis Bacon, there are 10 paintings for $900 and 100 people want them. Then there are 10 paintings for $2,000 and 100 people want them. With every price increase, 100 people still want them. Now there are 10 for $300,000 and still 100 people want them. The early sprays by Olitski will sell for three times as much as new ones because the early ones all have homes — have been bought and are therefore rarely on the market. I have a new artist now with his first one-man show, Andy Spence, and we priced his works at $1,000, $1,400 and $1,600, with flexibility 10%, because they are different sizes. An artist can’t make money on a show with these low prices and neither can I. I need $10,000 a month overhead. I have to sell $10,000 a week to break even.

What commission do you take?

I take 50% on a young artist. It becomes less, 40% dealer-50% artist, when the average price of the artist’s pieces goes over $5,000. Tom Holland is still 50% as his average price is just $5,000. With a better known, higher priced artist like Sam Francis, the commission is 25% with 75% to the artist.

What has led to your success?

I’ve worked hard, been smart and lucky — lucky in what I’ve shown. I have to make $500,000 in sales a year to break even. One-third commission is the average for my artists. I live on $25,000 a year. I’ve had years where I’ve sold a million and a half.

What about residual rights for artists?

If an artist is careful, he doesn’t need residual rights. Olitski, for example, is quite prolific and keeps half of his paintings. He lets out only a certain amount to keep up the scarcity. The artist’s best nontaxable income is the artist’s own work. An artist is poor who sells all his work because as the earlier styles rise in value through scarcity, he has none left. If he keeps some of each period, he can sell them later at increased prices and doesn’t need residual rights.

How do you run your business?

When I first began my gallery, I used to use artist’s sales to run the business and paid up before I got caught. Now I pay my artists instantly because it is done by my business manager. An art dealer makes money on what he doesn’t sell. I often buy an artist’s work now because I feel I can’t afford it later after it will go up in price. I recently bought a Westermann. It was a bargain because Westermann is lower in price than he should be and is bound to go up. I saw three artists today.

I thought you saw seven.

I was lying. I saw three. The artists are nervous when I visit them and the dealer is nervous. There’ve been years I’ve gone $200,000 in debt.

Did that make you nervous?

Yes. There is a lot of attrition in the profession of art dealer. The dealer is paid last — yet those who are wealthy to begin with often don’t last, except [Sydney] Janis.

What was your background?

I was a law student, then switched to art history at Stanford. I planned to get a Ph.D. But while I was working on my M.A. at Stanford to get into Columbia my advisor died. This was going to delay me for a year, so I had to get a job in an art gallery, and liked the money I made.

What is the function of a dealer?

Part of the function of a dealer is to look at the work of unshown artists.

Is that how artists get into your gallery?

I try to look at least at the slides of every artist that asks me, but out of the 100 or so artists I have shown in my gallery, I have shown only two who came in with slides and weren’t recommended by other artists.

Then an artist has to be recommended by one of your artists?

Not just my artists. I’ve taken artists on that were recommended by artists other than I’ve shown.

How do you feel about conceptual art?

To interest me, conceptual art must involve magic. It can’t be just autobiographical because every artist has done that throughout art history. It has to make me have feelings of my own about it. I like Walter de Maria. He did a post with a gold ball on top. The post was just tall enough and the room just small enough so the viewer never could see the gold ball — so I had feelings of my own about it. A lot of concept art is boring. Some is valid: that which uses words, notjust as a visual image but also in terms of what it does to you as viewer. Alex Smith and Al Ruppersberg are two artists currently showing who fulfill this criterion. Concept art should transform the experience of writing the words out; it should have the visual impact along with what it does to you. I feel that there are no movements in art, just good artists that do them.

What makes you visit an artist’s studio the first time?

I have to see something first — a show or slides to show that the artist is serious enough and doing enough things to make a visit worthwhile. I have limited time for that as I’m up at 7:30 a.m. to do European things until 9 a.m. Then I do New York things until 11 a.m. because of the time lag so I can phone them during their business hours. Then I get to the gallery about11:30 a.m.

What is the purpose of an opening? To sell?

An opening is a reception for the artist and his friends. It costs $500. I rarely sell at openings. Yet I have 20% to 30% soldout shows by the end of the opening. Buying at openings, sell-outs — is hysteria buying and the works usually wind up at auctions at much lower prices.

How do you expand your group of clients?

Be in my gallery as much as possible because they buy usually only when I’m there. I now have a woman working for me, Patty Faure, who is very good. She can sell and advise to buy and not to buy. The gallery is most important to the artist currently showing and next to the one just before and after, because I have the space to do a large backroom business.

What caused Pasadena’s changeover and what effect will it have on the art world and why?

Some reneged on pledges of financial support when they built their new museum; and also, because of the recession, the weight fell on a dozen people who shelled out $10,000 a month of their own money to keep it going. There are two things that hurt local artist the most: first, the institutions that drained money off of people who otherwise would have bought local art. Second, Gemini with their print market which popularized the well-known artist’s $200 print rather than the new artist’s unique work. As for [Norton] Simon taking over — he was the only option. The other alternative was closing. It’s the end of an era.

Do you show only certain contemporary trends?

Well, next September I’m going to show an artist who’s just beginning to show. He’s 50 years old and paints like Titian. He does strange truncated nudes. His name is Horatio Torres. He just had a show in New York.

What did you mean by corruption in the art world being due primarily to the artist?

Well, an artist came to me and said, “I’ve been offered a show in ‘X’ local gallery, but she doesn’t show good people. I want to wait and show with you.” I advised her, “Don’t wait. Show there. She has a good platform.” She said, “I want to wait.” I told her, “You’re corrupt” — in a nice way of course.

How should artists approach a dealer to show their work?

Ask questions politely: when would be a good time? Don’t interrupt their business. Don’t bug them. Sometimes people can walk in cold and it’s a good time and someone else can have an appointment and it’s not a good time. Some artists are so inconsiderate that they will grab hold of a dealer’s arm to get him to keep an appointment when it’s obvious that he’s involved with an important client. Dealers need privacy too. Once on a Sunday, I left my gallery to walk eight blocks to a friend’s house and six artists along the way asked me to see their work.

What else led to your success as a dealer?

Very much the same things that promoted me as a person. Such as what I’ve shown earlier, like Agnes Martin, bought at $13,000 and now it’s worth $50,000 — this gains me the respect of other dealers. I help museums. I tell them what to look at because they don’t know. They now ask me for Agnes Martins at $50,000, when earlier I couldn’t get them to buy them at $10,000. They know I know where those works are owned.

What led to the collapse of the print market?

Mainly oversaturation. Rarity makes prices go up. Many people collect art for the wrong reasons, social, monetary. It’s best to buy unique things. The multiple image was good for many people to have an art work. It made art open and not just for the elite.

Are many artists living off their work?

Very few artists live off their work. There are about 100,000 artists living off their work. The hardest people on artists are other artists. When one artist gets a grant or makes a good sale, other artists complain that it wasn’t deserved, that they should have gotten it, instead of being pleased that one of them did well. Such as photorealism: I think it’s a fad, so I’m glad Estes is making it now.

Do you ever wish you hadn’t been a dealer?

I’ve never worked a day in my life, and I’ve never had a vacation since I’ve been in this business. If I went and sat on a desert island for a week, I’d probably go stark, raving mad. The only times I don’t think about it are when I get drunk or when I’m having sex, but I think about it when I’m in a hot shower. I’m fortunate in that I love my work.

What’s more important, money or art?

If I had a lot of money, I’d probably spend it on art. The commodity part turns me off. That’s why I didn’t like the print thing. I think Los Angeles is on an upswing. Inflation helped the art market. There is more of interest going on in Los Angeles now in the studios than in New York. The stock market is unsafe and people want things around they like, so they buy art. I think the tax loophole for donations to museums is good. I just bought a Westermann and an Alex Smith. My interest is in availability, so I sell my older things like Kline, to buy newer, cheaper things that will go up. They’re still mine after I sell them. Whatever I once owned, I still psychologically own.