Reach for essence of thought, and the mark follows.

With Philip Guston in art world news recently, apparently because of the controversial acquisition of a large number of his paintings by the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, I thought I would relate my own experience of meeting Guston in 1963, what I learned from him, and my philosophical musings about our painting styles.

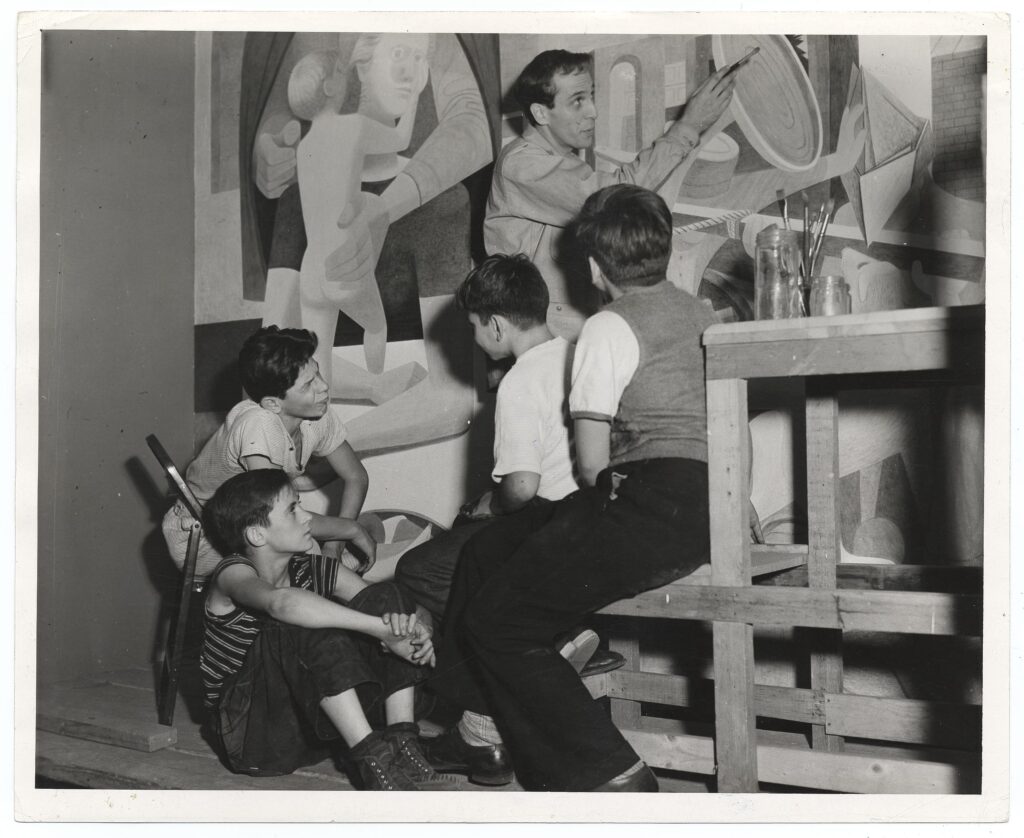

Photo of Philip Guston with mural, talking with children. By Sol Libsohn, 1940. Archives of American Art / Wikimedia Commons

Guston had been a WPA painter when he was young. He painted in the abstract expressionist style for a while, then had a mid-career transition and started painting things like his controversial, socially-conscious paintings of people wearing KKK hoods. He was a Jungian. He went back to painting clubs (maces) and flatirons and delightfully ugly things.

I had been awarded a scholarship to the Yale Norfolk School of Art during their summer program in 1963. Philip Guston was a featured guest artist at the school that summer. He decided to give his lecture on the campus lawn sitting in a folding chair, holding court for five hours. All 30 of the summer school students were there at the beginning, but by the time Guston was finished talking, there were only four of five of us left, including me.

One of the good takeaways from Guston’s talk was his description of how he painted. He told us he typically walked up to a canvas on the wall, stood flat-footed, and painted for thirty minutes without stepping back to look, the way most people do. After that he would go and make a cup of coffee, walk back, sit a good distance away, and look at the painting for another 30 minutes or more. He then approached the canvas again and stood flat-footed, making marks for another 30 minutes. In other words, he advised not looking at your expressionist painting while making it.

He emphasized thought first, then make your mark. Reach for essence of thought and the mark follows; make each mark with great intent. The idea and the mark should be the same.

He also said that when he thought of blue, he would reach for orange. In reaching for paint, jars became the thought.

Consistent with what I learned from Guston, art critic and curator Robert Storr wrote that Guston experienced a strong urge to paint very quickly without even a brief time interval to reach between paint cans, palette, and canvas. The urge became so strong that he would make himself stand and work almost frantically without stopping, and without backing up to look at what he was painting. (From Storr’s book Guston, New York, 1986, p. 25.)

Here is a link to a Christie’s lot essay that elaborates on Guston’s paintings and the development of his technique.

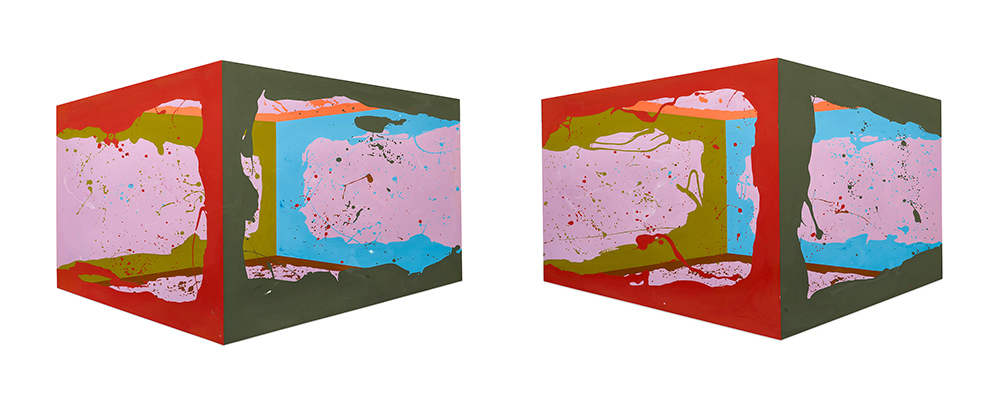

Ronald Davis – “Outside C’s,” 1969. Diptych, shaped. Each panel: 33 x 47 ½ inches. Molded polyester resin and fiberglass

In my own work, specifically my illusionary polyester resin and fiberglass paintings, I didn’t get to look at the painting until it was done, after I pulled it off the mold, because I painted them from front to back, sight unseen — standing flat-footed.

In painting my 3D illusions, backwards, it forced a spatial depth that couldn’t be violated. I always started with a cartoon mockup of these resin paintings, a small line drawing on acetate or paper, sometimes colored-in with cel-vinyl acrylics. The cartoon mockup was enlarged (not projected) by marking the voxels of each shape’s edges onto the waxed mold that was built on a formica table, taping the edges, and applying layers of colored polyester resin (as paint). The last layer was fiberglass cloth laid directly behind the resin, analagous to canvas as a support.

Guston’s advice foreshadowed what I would come to learn from my own experience in the studio, which is that making a painting is very different from looking at a painting.